233 years ago, on January 21, 1793, at 10:15 am, Louis XVI, the fallen king of France, walked up the wooden steps in the middle of the Place de la République, and with the quick release of the blade, he was dead.

Born at the Chateau de Versailles on August 23, 1754, Louis-Auguste became the Dauphin of France when his father died in 1765, and became the heir to his grandfather Louis XV’s throne at the age of 11.

A young boy who preferred books, keys, and maps found himself getting married at 15.

In the very early morning of May 16, 1770, Marie Antoinette headed to Versailles. Arriving at 10 am, she entered the golden gates and was taken to the queen’s apartment to get ready. A beautiful dress, two sizes too small, of silver fabric, which was the customary color for the Dauphine to be married in, was waiting for her.

Louis XV and his grandson Louis-Auguste waited in the king’s apartment. Dressed in gold and wearing a diamond-covered habit of the Order of the Holy Spirit. Just before noon, he met his bride and took her hand. The two walked through the Hall of Mirrors on their way to the Royal Chapel, built in 1699 by Louis XIV. Her gown and all its jewels shone brighter than the mirrors themselves.

In the Royal Chapel, they kneeled before the Archbishop of Reims, Monseigneur de la Roche-Aymon, blessed the rings and 13 gold coins before Louis placed the ring on her tiny finger. The wedding was followed by a lavish feast in the Royal Opera attended by the entire court.

A firework display was to follow, but was canceled due to a storm and rescheduled to May 30 at the Place Louis XV in Paris. The celebration of the marriage and the fireworks took place before thousands of onlookers. A fire broke out on the scaffolding, sending fireworks flying and people running in panic. 132 people died, and many more were hurt, a bad omen for the start of their lives. Place Louis XV was renamed Place de la Revolution and in 1793, the couple would meet their final fate under the guillotine’s blade.

It would take 8 years for the marriage to be consummated, and 11 years for the all-important heir to the throne, bringing in much speculation and pressure from both sides of the family.

Upon the death of Louis XV on May 10, 1774, the young couple was crowned king and queen of France. Inheriting the crown also meant taking on the country's swiftly mounting debt and the resentment of the monarchy.

The quiet Louis XVI was more focused on religious freedom and foreign policy than the plight of the citizens, and wanted to be admired and loved by the people.

On October 1 and 3, 1789, King Louis XVI threw a large dinner party for the king's guards and the Flanders Regiments. While the people of Paris were starving and unable to get bread, a lavish dinner at Versailles was the final straw.

Before dawn on October 5, a large group, mostly composed of women, met in front of the Hotel de Ville. Breaking in and stealing more than 600 weapons, the group marched from Paris.

In the pouring rain for over 5 hours, they walked in the mud, arriving at Versailles. Demanding to be let into the National Assembly, their spokesperson, Stanislas Maillard, read their demands for wheat, flour, and an end to the blockade of the route into Paris. With all in agreement, the order was taken to the king to sign and enact, but it was too late. We could be done with this story, but we know it ends differently.

Overnight, the crowd gathering outside grew restless after endless hours without any news, prompting the guards to push back. The angry mob rushed the palace, killing the queen’s guards and calling out her name through the gilded halls of the palace. The royal family finally agreed to go with the crowd back to Paris, leaving Versailles on October 6 and the life they knew behind.

Their prison was the Palais des Tuileries, where they could be watched closely, but still lived a life of comfort for over two years.

On June 21, 1791, the king and queen of France attempted a last-ditch effort to escape from the watchful eyes of the Tuileries. The king had been cooking up the idea for over a year and discovered that the French town of Montmédy, near the edge of Luxembourg, was an area that still supported the idea of the monarchy.

Axel Von Fersen, Marie Antoinette’s close friend and lover, worked on the route, plans, passports, and the family's carriage. Axel first met Marie Antoinette in Paris on January 30, 1774, at a masked ball. Behind the mask, he had no idea he was talking to the future queen of France. The two would meet again after his return from America, and they remained very close until the end. Historians have often wondered if it was more than that, but recent deciphering of their private letters gave more evidence to the fact that the two were also lovers.

Fersen borrowed 300,000 pieces of gold from a wealthy woman to help fund the family's evacuation and had a lavish carriage made for the royal couple, complete with a toilet.

Louis XVI, Marie Antoinette, their two children, and Madame Elisabeth, the sister of the king. Armed with fake papers, they were now the staff of the Baroness de Korff, a Russian widow on their way to Frankfurt. On the night of the escape, the family left behind their formal attire and dressed as servants.

At 10:50 pm on June 21, 1791, Fersen took the royal children out of the Tuileries and safely tucked them into the awaiting coach. At 11:30 p.m., Louis XVI & Marie Antoinette said their goodnights and went to bed. Louis had spent most of the day hidden away writing a 16-page “political will,” a declaration that would later seal his fate.

At 12:10 am on June 22, Louis and Marie left the Tuileries through separate doors, alone. Louis found his way to the nearby Rue de l’Échelle, where his children, Fersen and the governess, were waiting. They all found the coach quickly, but Marie Antoinette got lost on the way and arrived 90 minutes late. The distance from the Tuileries today to where the coach was is less than 7 minutes. When the family was finally together, they headed to the Quai du Louvre, where the carriage was to meet them along with a team of loyal soldiers. Although they were already close to two hours late, they had to wait for another hour for the carriage to arrive. This delay would also cost them immensely.

The governess was not in the original plans, but refused to leave the children. Her job was to care for the royal children until her death, and she was not backing down. She took the place of one of the only tactions in the group that knew the roads of France. The men chosen for the voyage were each selected for their loyalty to the family, not necessarily for their abilities. Another foolish mistake.

Fersen stayed with them until Bondy, where he was replaced by a new driver, to avoid adding too much suspicion back at the palace. Along the route, royalist supporters were strategically placed to change out the horses and protect them, but with no way to reach them and close to three hours behind, many left fearing the worst.

Once on the road, now 3 hours late, they arrived at Pont-de-Somme-Vesle SE of Reims.

At the next town, Montmirail, at 11 am, the king was recognized. Meanwhile, back in Paris, at 7 am, it was discovered that the family was gone, leaving only the king's “political will,” which enraged Lafayette, who was supposed to watch over them. He immediately let it be known they were gone and issued an arrest warrant.

Just before 8 pm in Sainte-Menehould, Jean-Baptiste Drouet thought the peasant woman looked a lot like Marie Antoinette. When he saw the king's profile in the window of the carriage, he knew it was Louis XVI. It matched the 50 note coin in his pocket. As they arrived at Varennes at 10:50 pm, the riders were not there to meet them. 20 minutes later, in front of the Eglise Saint-Gengoult, the citizens demanded that they exit the carriage. At 11:10 pm, just 24 hours after their escape, they were arrested.

On the morning of June 22, the National Guard was on its way back to Paris. The route would take four days; they drew it out so people could see it and be taken back to Paris. From Chalons-en-Champagne on the 22nd, Epernay on the 23rd, and to Meux for the night of the 24th. I doubt they were able to enjoy the Champagne and Brie de Meux on the way.

On June 25 at 7 am, they left Meux for their last trip to Paris. Hundreds lined the streets of Paris to welcome them home. They were told that if they cheered for the king, they would be beaten, and if they yelled insults, they would be hanged. People behaved until they saw the Queen, who was always the brunt of their anger. Yelling and chasing their carriage down the Champs Élysées until they entered the Tuileries.

Now more closely watched and their movements limited to their bedrooms and dining room, while the people outside the palace became angrier and angrier. Had they not escaped, the family would have spent the rest of their life in prison.

At 5 am on August 10, 1792, it came to a boil. The Tuileries were stormed, the Swiss guards were killed, and the royal family ran for their lives through the garden. More than 1000 people were killed on this day, the palace was looted, and the interior was destroyed.

Arriving at the Assembly on the edge of the garden, in the former stables used for Louis XV, where the king would be tried in a few short months. The king was given wine and treated like a king. Marie and her children were put into a small, locked room. That night as they ran, the monarchy slipped through their fingers.

On August 13, they were sent to the Temple prison in a cold, dark tower. The king and his valet Jean-Baptiste Cléry were separated from his wife, children, and sister, but still able to visit each other.

A month later, on September 21, the monarchy was abolished.

On October 1, just three years after the lavish party thrown for his guards, it was decided to establish a commission to bring the king to trial and answer for his crimes. The verdict was written before the trial ever began.

Louis XVI, now known as Louis Capet or Citizen Capet, faced the wrath and agenda of Robespierre and his Terror friends. Not much evidence was found to be used against the king, which, of course, didn’t matter. In the third week of the investigation, an iron-lined cabinet was discovered hidden in a wall of the Palais des Tuileries. His opponents divulged papers showing that the king was conspiring with foreign powers and a testament to his guilt. To date, no evidence of this has been discovered.

At the start of December, the calls for his death began, led by Robespierre. “He must die so his homeland can live.”

The trial started on December 11, 1792, at 11 am in the Salle du Manège, where he and his family sought refuge just four months before.

Standing before the sham court and accused of the massacre of the Tuileries. Betraying his oath to the French people, supporting priests, and colluding with foreign powers. Always claiming his innocence, but still treated with more respect than they will give his wife ten months later.

For a month, they heard from witnesses and lawyers who stacked the deck against the king. On January 16, 1793, the first votes were counted. For his immediate death, 366 people, including Jacques-Louis David, Robespierre, Marat, Camille Desmoulins, and Philippe Égalité, cousin to the king. The vote was cast three times, with the final determination made on January 20, 1793, with 380 voting for his immediate death.

Each day of the trial, he returned to the Temple prison and kept away from his family. On the evening of January 20, he held his children one last time and said goodbye to his wife and sister, who collapsed in despair.

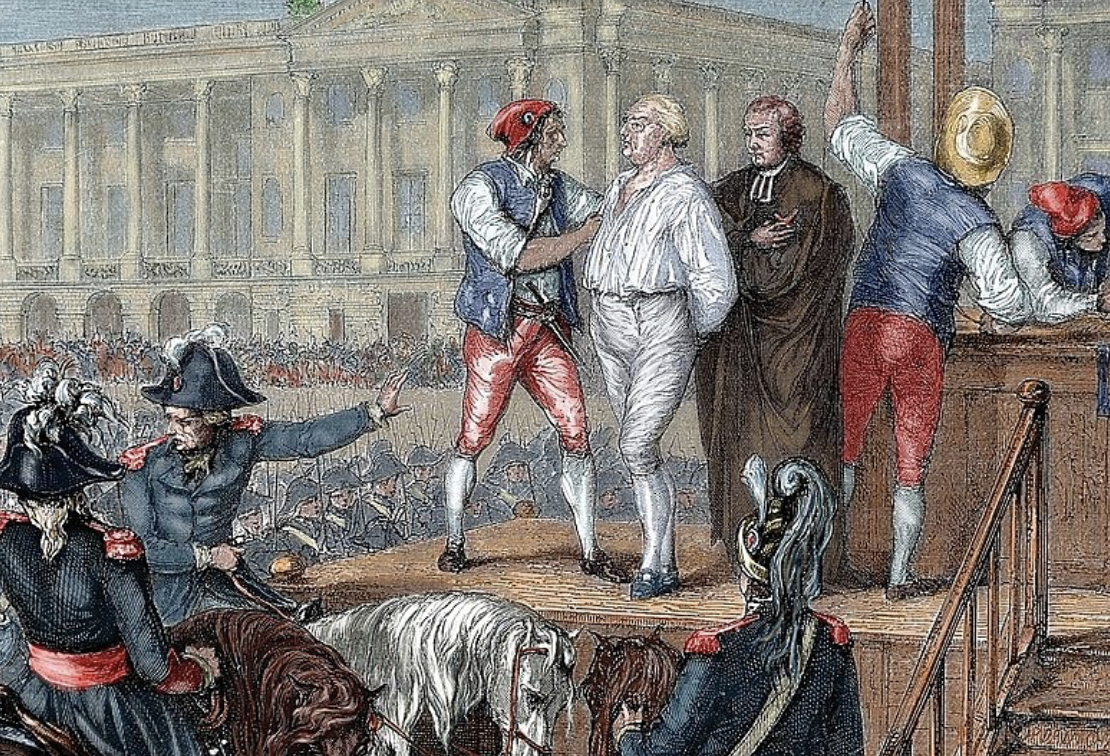

At 9 am on Monday, January 21, 1793, Louis Capet left the Temple prison and his family behind. The slow drive through the city, held inside a verte wagon carriage, took over an hour. The people lined the route, yelling and proclaiming victory for the Revolutionists.

Baron de Betz, a loyal supporter, plotted a last-ditch escape plan. Grabbing the king along the route and hid him in a house before they could get him out of the city. Unfortunately, his co-inspirers didn’t show up and alter history.

In the northwest corner of the Place de la Révolution at 10:15 am, the fallen king walked up the scaffold to the screams of the thousands waiting to bear witness to the death of the king and all he stood for.

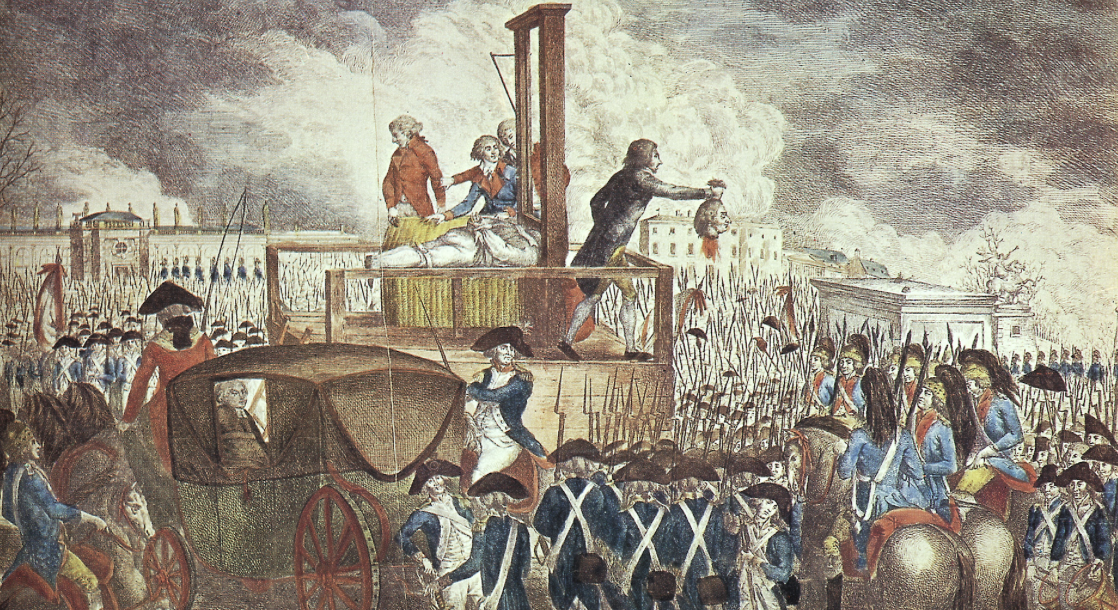

Louis Capet stood before his executioner, Charles Henri Sanson, while they cut his hair, tied his hands, and removed his cravat. The last words the king would say were to profess his innocence. At 10:22 am, the blade fell, marking the end of Louis XVI.

In the moments after his death, his head was hoisted up so the crowd of thousands of people in the Place de la Révolution could see that the blood of the king had been spilled. Quickly after, executioner Sanson placed his body into a cart that was taken to the nearby Madeleine church and cemetery.

Back at the Temple prison, Marie Antoinette, her sister-in-law Elisabeth, and her two children heard the sounds of cannons and people rejoicing in the distance. At that moment, they knew Louis XVI was dead.

A brief ceremony of the church vicars was held, and his body was placed into a deep grave, his head placed between his feet and covered with lime. The Cimetière Madeleine was a short walk from the church, and Pierre-Louis Descloseaux overlooked the plot from a nearby building. Pierre kept an eye on the spot where the king was laid to rest, and in ten months, where Marie Antoinette would also join him.

When Louis XVIII, brother of the slain king, came to power in 1814, Descloseaux contacted him and told him where, in the now-defunct cemetery, he could find his family. Their only surviving child, Marie-Thérèse, Duchesse d’Angouleme, returned to Paris and the final resting place of her parents.

Every day she returned, sitting for hours. Louis XVIII announced that a chapel would be built in their memory, and Marie helped pay for the construction and the two statues of her parents in the upper chapel.

Just opposite the statue of Marie Antoinette in the Greek cross chapel is the statue by Francois-Joseph Bosio, Apotheosis of Louis XVI. Louis is dressed in his coronation robe with fleur de lys, as the angel points his way to heaven, and his last will and testament is engraved on the marble pedestal.

The most poignant part of the monument is in the crypt below. In a small chapel, a black and white marble altar that marks the exact spot where they had spent 22 years in an unmarked grave. A beautiful stained glass window lets in the softest light as you quietly take in the moment. Imagine Marie-Thérèse visiting this same spot every day with her parents, whom she lost too soon.

On January 18 & 19, 1815, Madame Elisabeth watched as the bodies of her parents were recovered from deep in the earth. On January 21, the 22nd anniversary of the death of Louis XVI, the couple was taken on their final route to the Basilique Saint Denis.

The procession of 3,000 people, made up of military, ministers, and distant family, traveled north past the edges of Paris. The boxes containing the bones of the king and queen were placed on a large carriage inside a grand sarcophagus. What a difference 22 years make, as now the people stood along the route for even a glimpse.

Upon arrival at the basilica, a large mass was held in front of the family and dignitaries before their bones were interred in the crypt below, alongside what is left of the past rulers that were recovered after the Revolution

On April 24, the king ordered the construction of a new chapel for the basilica, dedicated to the couple. Edme Gaulle was commissioned to sculpt the statue of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette, Pierre Petitot. The chapel as imagined never came to be, but the statues can be seen today, and I will never forget the first time I saw them.

On that date in 1815, Louis XVIII ordered that each year they hold a special mass on the Sunday closest to the death of Louis at Saint Denis. In 202,0 I was lucky enough to attend a mass on a very chilly morning outside the Chapel Experatoir. In attendance was Louis XX, the man who would be king if France still had a monarchy. Each year, a mass is also held at Eglise Saint Germain l’Auxerrois,s where the other pretender to the throne and descendant of Philippe Égalité, Jean d’Orléans, le comte de Paris, is in attendance. Since his forefather voted for the death of Louis XVI, should he really be there?

Do you know that every single day you are in Paris, and just around every corner is a small reminder of that fateful day, January 21, 1793?

Did you notice how I gave you the color of Louis’ carriage to his death? All over Paris, from the benches in the parks to the lampposts to the bouquinistes and more, everything is painted a very specific color: vert wagon. The same color as the last transport of Louis XVI. A little odd of a reminder, but the color also blends into the park's trees and bushes.

And now you know.

Visit many of these spots on your own when in Paris, or contact me to take you on a private customized walk through the streets of Paris, pointing out the many locations tied to his historic period.