Listen to the newest episode today

In 1772, King Louis XV commissioned Boehmer & Bassange, the crown jewelers, to design a special one-of-a-kind necklace to "surpass all others” for his mistress, Madame du Barry.

Charles Auguste Boehmer and Paul Bassenge, known as the Bohemians, had an atelier in the Place Louis le Grand, today's Place Vendôme. The two became the jeweler to the king after Thierre de Ville d’Avry, the minister of the king’s household, believed that he should have the full authority over the appraisal of any jewels created or used from the Crown stones. Jeweler Aubert decided he wasn’t going to work under these conditions under Louis XVI and gave up his royal marker, allowing the “Bohemians” to step right in.

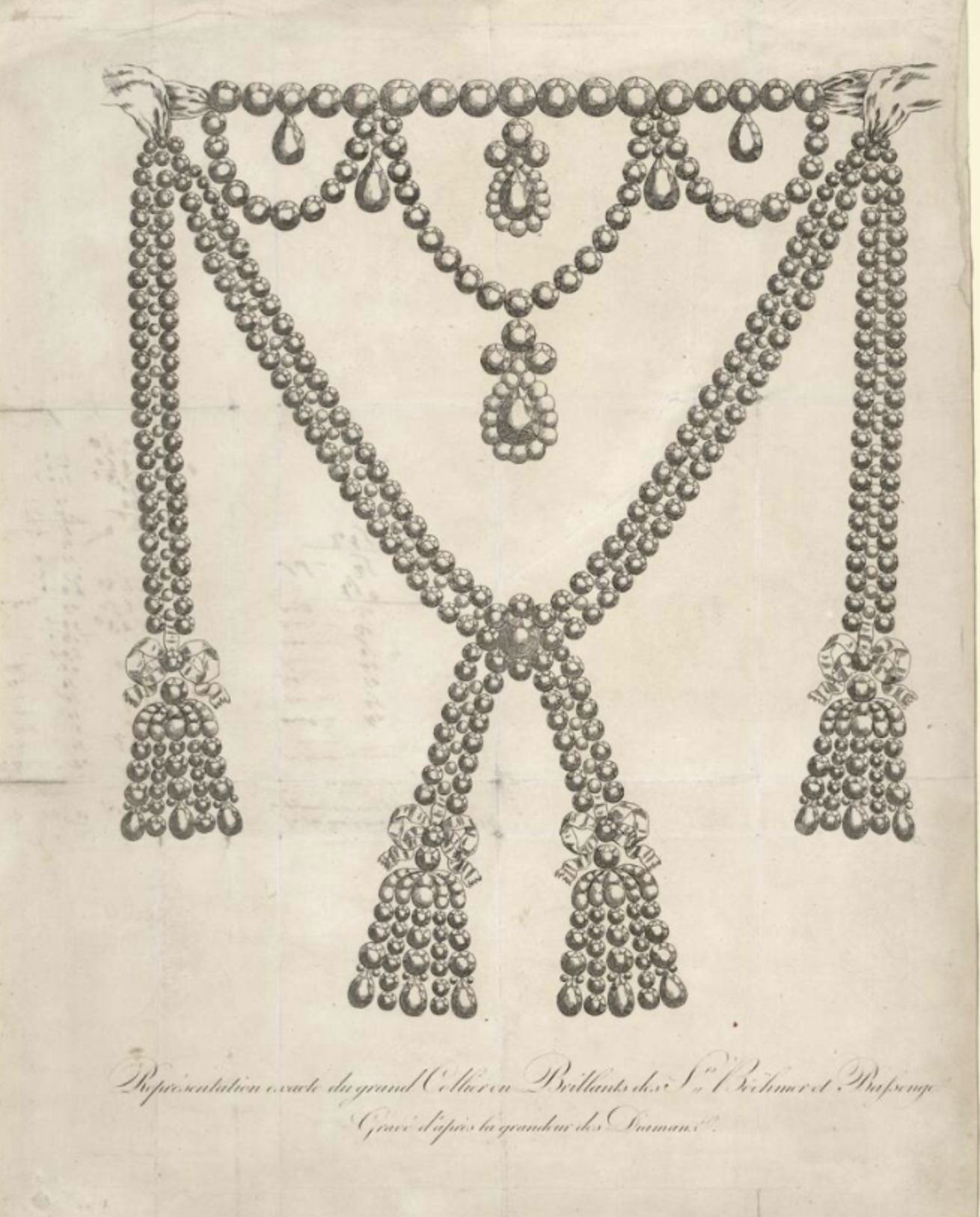

It took six years to gather the 647 diamonds weighing 2,840 carats; Louis XV would die, and du Barry would be banished before it was finished in 1778.

Described as a row of 17 diamonds, each of 5 to 11 carats, that ties on the neck with a black silk ribbon. Three garlands hang down with two large pear-shaped diamonds, a cluster of 3 diamonds and large pear drop, and a larger pear diamond surrounded by smaller diamonds that it also hangs from.

What really makes this necklace stand out are the wide “ribbons” and tassels made of more than 600 diamonds. The tassels later inspired Empress Eugenie and the bow brooch stolen from the Louvre.

Left with a very expensive necklace on their hands without being paid, they reached out to Louis XVI, thinking he would want to buy it for his queen. With a very high price tag, the queen refused, telling her husband, “We have more need of 24 ships”. However, it was also her strong dislike of du Barry, and she didn’t want anything intended for her. The jewelers were distraught, would be bankrupt if they couldn’t sell the necklace, and were easy prey for a crafty criminal.

Jeanne de Valois Saint Rémy, Comtesse de la Motte, began her life believing she was descended from royalty. Her father, Jacques de Valois, was the illegitimate grandson of King Henri II and his mistress Nicole de Savigny. Never recognized, they constantly lived far beneath where they believed they should be, and by the time Jeanne grew up, she wanted to do something about it.

At 24, Jeanne married Nicolas de la Motte and both had a lofty goal of how their life should be. Nicolas obtained a job as a bodyguard to the Comte d’Artois, brother of Louis XVI and future king Charles X. Allowing Jeanne entry to Versailles amongst the court, she planned to get close enough to Marie Antoinette, who she believed would take pity on her circumstances as a woman and bestow her with her regal heritage. This, of course, did not happen.

Jeanne met Marc Antoine Rétaux de Villette, a jack of all trades, including forgery, prostitution, and fraud. A friend of her husband's, the two began a hot, steamy relationship and hatched a plan to get what she believed she rightfully deserved.

Jeanne de la Motte Valois Saint Remy by Vigee le Brun

Our other major player in this story was Cardinal Louis-René de Rohan. Descending from the wealthy Rohan family, he served as an ambassador to Vienna in 1771. Empress and mother to Marie Antoinette, Marie Therese wasn’t a fan of Rohan. Rohan loved his life of luxury and being surrounded by lovely ladies and had little interest in much else. Rohan uncovered a plot by the Empress to overthrow Poland and wrote a letter exposing her. The letter made its way to Versailles and into the hands of Madame du Barry, who read it aloud at a dinner with Marie Antoinette looking on. She would never forgive Rohan for what he said, and another strike against du Barry.

Rétaux de Villette had learned of Rohan’s desire to return to the good graces of the young queen through a few of his ladies he employed to service the Cardinal. With his talent for forgery, access to the palace, and a knack for pulling off a sting, a plan was hatched, and the Cardinal was the perfect tool.

Jeanne placed herself in the path of Rohan a few times until he noticed her, and the two became lovers. Confessing his distress over his lack of a relationship with the queen to Jeanne. At the perfect moment, she told him she was friends with the Queen and that if he wrote her a letter, she would get it to her. Jeanne had another agenda. Villette answered the letters himself, posing as the Queen, who then passed the letter to the Cardinal by Jeanne.

Cardinal Rohan

Growing increasingly skeptical after numerous letters, Rohan begged for a private meeting with the Queen. Jeanne hired Nicole Le Gray d’Oliva, a prostitute from the Palais Royal, to impersonate the Queen. On August 11, 1784, at 11 pm, in the Grove of Venus at Versailles. The “queen” emerged and handed Rohan a red rose. For the next few months, the letters from the “queen” to Rohan continued.

On December 28, 1784, Jeanne visited Boehmer & Bassange. Her reputation as a close confidant of Marie Antoinette had spread through Paris, and the jewellers were hoping she could help them.

On January 21, 1785, Jeanne told Rohan that the Queen wanted the necklace but needed someone to get it for her. Jeanne forged a letter and a purchase order for the necklace, and he took it to Boehmer & Bassange on February 1, 1785. Handing over the necklace to Rohan, he then took it to meet Jeanne and what he thought was one of the Queen’s valets. It was Rétaux de Villette who promptly took the necklace and removed all the diamonds. The jewels were separated between de Villette and her husband, de la Motte, and instructed not to sell too many at once.

Nicolas de la Motte fled to England with the largest of the diamonds. Dressed as an aristocratic gentleman, he claimed the diamonds were from belt buckles and family heirlooms. In need of a quick sale, de la Motte offered the stunning diamonds at a very low price that would raise suspicion among jewelers. Numerous jewellers called the French embassy, but there hadn’t been any reports of high-quality gems missing. De la Motte realised he might have better luck trading them instead of selling. Furniture, crystal chandeliers, bronze and marble statues, and art, he loaded up and returned to France.

For almost eight months, the trio lived a life of luxury. Jeanne’s husband returned to England, and Jeanne and Villette lived in a large house in Bar-sur-Aube, which they had acquired through the sale of the jewels.

The first payment to Boehmer & Bassange was due on August 1, and as the days passed, they grew more wary that they wouldn’t see the money. Meanwhile, Rohan still wasn’t being invited back into the fold, and the confidence of the queen. The jewelers contacted Rohan, who was unaware they hadn’t been paid. After days of trying to reach Jeanne, she told him the queen needed money and that he could help her find wealthy friends who would make the first payment.

This was when her grand scheme began to unravel. As jewelers to the crown, they knew many people in the court of Versailles. They had been told to keep the entire episode a secret as Marie Antoinette didn’t want anyone to know.

Boehmer sent a letter to a chambermaid of the queen, revealing his situation. The letter was then passed to Madame Campan, who told the Queen, and then to the Baron de Breteuil, minister of the King's household, who had a strong dislike for the Cardinal.

On August 15, 1785, on the Feast of the Assumption, the Cardinal was walking through the Hall of Mirrors when he was arrested and taken to the King. Marie Antoinette and jeweler Boehmer were waiting with the order signed by the Queen. She had never seen it before. Rohan was taken to the Bastille and divulged all he knew about the necklace theft.

Jeanne and Villette continued to sell the jewels one by one.

Villette approached a jeweler in Montmartre, offering a few of the large, brilliant-cut stones at very low prices, which struck the jeweler as odd. The police were alerted and paid a visit to Villette's apartment on the Île Saint-Louis. The jewels were gone, but he was arrested, confessed, and also admitted the involvement of the de la Motte couple.

Jeanne de la Motte was arrested and sent to the Bastille.

Nicole Le Gray d’Oliva, the prostitute that impersinated the queen waq arrested in Brussels on October 16, 1785.

L’Affair de Collier de la Riene 1946

On May 22, 1786, they all stood trial together at the Parliament of Paris on the Ile de la Cité. Eight days later, on May 30, the verdict was in. Cardinal Rohan and Nicole Le Gray d’Oliva were acquitted of all charges.

Nicolas de la Motte, who never appeared at court, was sentenced to life in prison in absentia. After the Revolution, he returned to France and supported himself by extorting the Rohan family into not publishing his memoirs.

Rétaux de la Villette was found guilty and banished from France. He made his way to Venice to write his memoir and the story of the Affair of the Necklace. He wasn’t the only one.

Jeanne de la Motte was found guilty and sentenced to life in prison at the Salpêtrière for the rest of her life. She was whipped and branded with the letter V for Volueuse, Theft. Two years later, she escaped from prison dressed as a boy and fled to London, where she would write her version of the story.

On August 23, 1791, in an attempt to evade creditors, she fell out of a window and died. The report stated that she was “terribly mangled, her left eye cut out, and her arm and both legs were broken.

For the Queen, who was innocent in the plot, it was too late. It only fed into the rumors of her excess. People even thought she orchestrated the entire thing to get back at Rohan. The Affair of the Diamond Necklace led to her final fall that was to come in just a few years.

As for the diamonds, they all disappeared. The jewelers went bankrupt due to the immense loss and embarrassment the theft caused them. To this day, we don’t officially know where any of them went. The thieves never gave up any information on who they sold the jewels to, leaving it a question that also brings a bit of deception.

A few of the detailed engraving by Boehmer & Bassange remain and have been used to recreate the necklace in faux stones. A replica made by jeweler Albert Guerrin for the Maison Burma in Paris in 1960, and donated to the Château de Versailles in 1963, is on display in the Queen's apartments, closed to the public except for special tours. I am going this week and will share everything I see.

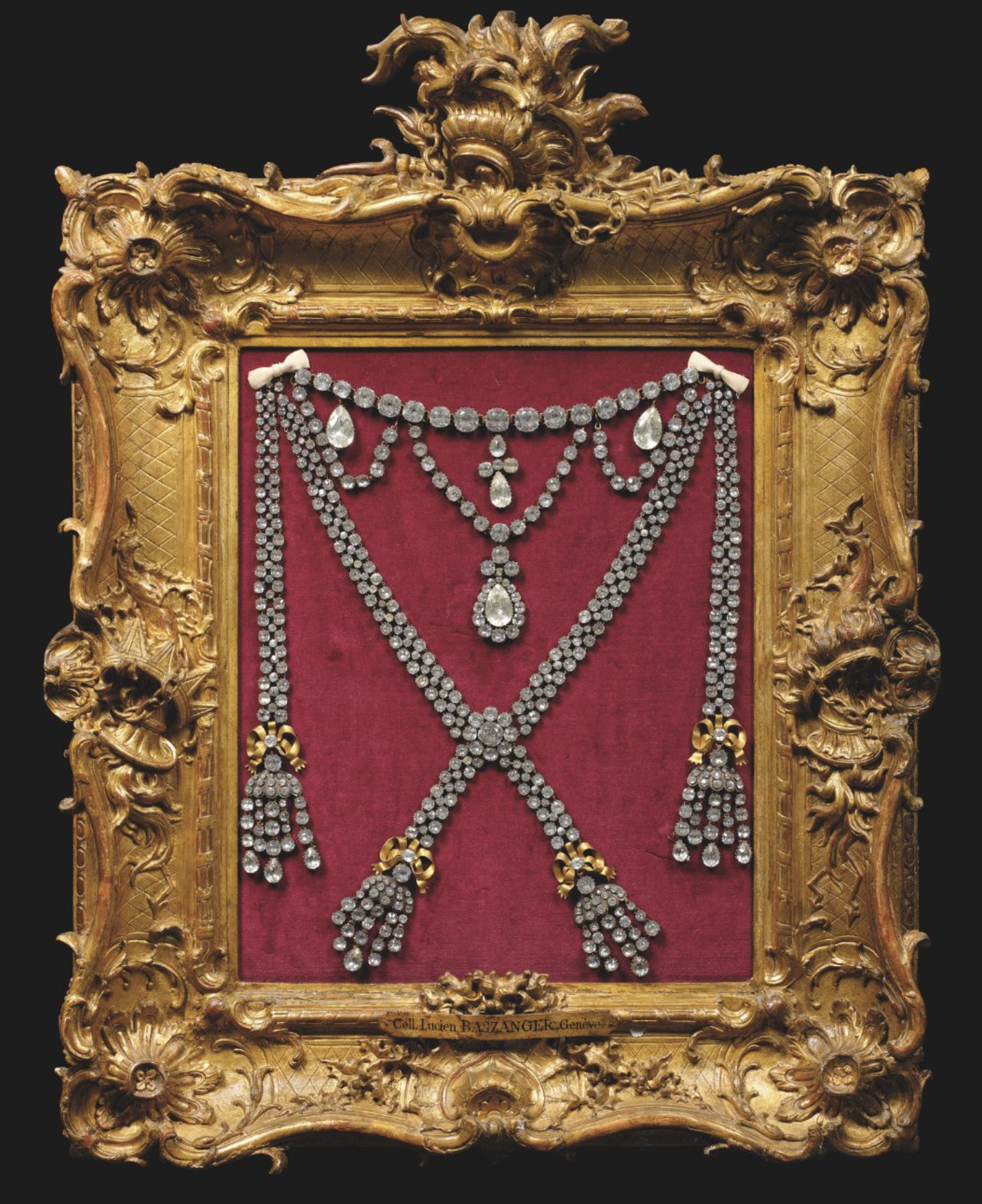

The oldest replica was created by Lucien Baszanger in the early 20th century and was recently sold at auction in Paris. Made of silver, metal alloy, and imitation diamonds was faithfully created from the original etching. Later copies added 49 pearls to the piece. At the auction, the replica sold for over 35 thousand euros.

Today, that real necklace would be worth over $17 million dollars.

Marie Antoinette has been accused of many things since the 18th century. Known for her lavish lifestyle and spending, in reality, the brother of Louis XIV, Philippe d’Orléans, spent more on shoes, clothes, and jewels than Marie Antoinette ever did.

Paintings of Marie Antoinette rarely depict her wearing necklaces. She was more fond of bracelets and earrings, and at large events would wear a few of the large Crown diamonds in her hair or hat, including the Sancy kept in the Louvre.

With each new king, the Crown Jewels would be inventoried. Many would sell them off, dismantle pieces, and recreate them in their own taste. Large gems were even recarved, making it even harder to track the provenance of many of them.

When Marie Antoinette arrived at the Court de Versailles, one of the only things she was allowed to bring with her were her jewels. Pieces given to her by her mother, Empress Marie Therese, and her grandfather-in-law, Louis XV, all became her personal collection, not of the Crown.

On May 5, 1789, was the last opportunity that Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette would wear their jewels. At a banquet of the opening of the Estates General at Versailles, the couple was decked out in silver and gold cloth, much like their wedding, and dripping in jewels. Sewn into her dress, on her hat, in his button holes, on the buckles of their shoes, and even the Regent diamond made an appearance on the king's hat.

Exactly five months later, on October 5, they would leave Versailles behind and be taken to Paris, and the march to their final moments that would end each of their lives in 1793.

At first, they lived a life of luxury in the Palais des Tuileries with all the comforts of royal life, including their jewels. Fearing the worst, Marie Antoinette began packing her belongings and giving them to trusted friends who would send them far from Paris.

Madame Campan writes in her memoir of an afternoon in the palace when she helped the queen load a diamond bracelet, rubies, and pearls into a small crate. The following day, they were taken by her hairdresser, Léonard, who personally delivered them to Belgium.

Belgium was under Austrian control at the time, and it was a safe place to ride out the Terror. The queen instructed Léonard to sell some of them as she and Louis XVI would need money. This was prior to the attempted escape in 1791. What remained of the jewels eventually reached the couple's only surviving child, Marie-Therese.

Upon Léonard’s return to Paris, he was given another box of jewels, which he hid away in his apartment and eventually took to London to sell on December 27, 1791.

Frequently, a piece of jewelry appears at an auction claiming to be created from the “Queen’s Necklace”. It always causes a buzz and is picked up by every news source and jewelry influencer. Sadly, none of them can be traced back to the actual necklace or the diamonds used to create it.

This goes for just about any piece that actually belonged to the queen.

One necklace attributed to Marie Antoinette was a stunning piece featuring 30 brilliant-cut diamonds and 13 pear-shaped diamonds in various sizes. It came up for auction at Christie’s in London in June 1971. It included four documents with detailed information on the provenance and former owners.

Belonging first to Marie Antoinette, it was given to her daughter and most likely in the box Léonard had taken to Belgium. Upon her death, it was left to her husband's niece, Marie Therese of Austria-Este. She later passed it to her niece, Marguerite, duchess of Madrid, who left it to Don Jaime de Bourbon after her death in 1893. It was then sold to the Archduchess Leopold Salvator, who passed it to Princess Massimo. The Princess then sold it in 1937 to an unknown buyer of a “princly family”. At some point, it was sold to an Indian merchant, who brought it to auction in 1971.

It did not meet the minimum bid, so the unknown owner kept it and dismantled it at that point.

The necklace is stunning, but the setting is in the style of Marie Antoinette and was most likely redesigned under Marie Therese of Austria-Este.

Another necklace that gains a lot of attention is called the Sutherland Diamond Riviere. Designed with 22 large diamonds. There are two versions of the history that can be linked to the Sutherlands and their descendants. George Leveson-Gower duke of Sutherland, served as the ambassador of France during the Revolution. At the time, the royal family was held in the Tuileries. Elisabeth, the Countess of Sutherland, claims to have grown close to Marie Antoinette and was given some of her jewels as they fled France and returned to England.

Another story was that the duke's father, Granville Leveson-Gower, the first Duke of Sutherland, purchased the diamonds from Nicolas de la Motte and claimed they were part of the famed necklace.

Worn by generations of Sutherland women, it came up for auction in 2019 but was removed and given to the British government in lieu of estate taxes, and is now held at the Victoria and Albert Museum.

In the Smithsonian in DC, a set of large pear-shaped drop earrings is also tied to her, although there isn’t any evidence to back that up. In fact, a letter written in 1928 by Prince Youssoupoff dates the jewels to his great-grandfather, who had purchased them on 1803 and was not affiliated at all with Marie Antoinette. Eventually, purchased by Marjory Meriwether Post through Harry Winston and later donated by her daughter to the Smithsonian.

With such an uncertainty of whatever happened to the Queen’s necklace or its diamonds or any of her other jewels, but we haven’t seen the last of the auction items or stories of jewels that “may have been” a part of the Queen's collection or the famous necklace.