In the early morning of February 6, 1661, a fire raged through what was described as “the most beautiful gallery in the world.” 350 years ago, a Sunday morning marked a turning point in the history of the Louvre in the same space that made news four months ago.

The year 1661 was pivotal in the life of Louis XIV; after the death of his closest advisor and godfather, Cardinal Mazarin, he would seize control of the government, and the grand story of the Sun King began. He was just 22 years old.

Before his death, Cardinal Mazarin influenced everything from the people who had access to the king to the design of royal buildings and the amassing of the royal collection. In the 1650s, with the architect Louis Le Vau, Mazarin sought to expand the Palais du Louvre to include a theater, library, and galleries for the king's paintings, sculptures, and other objects.

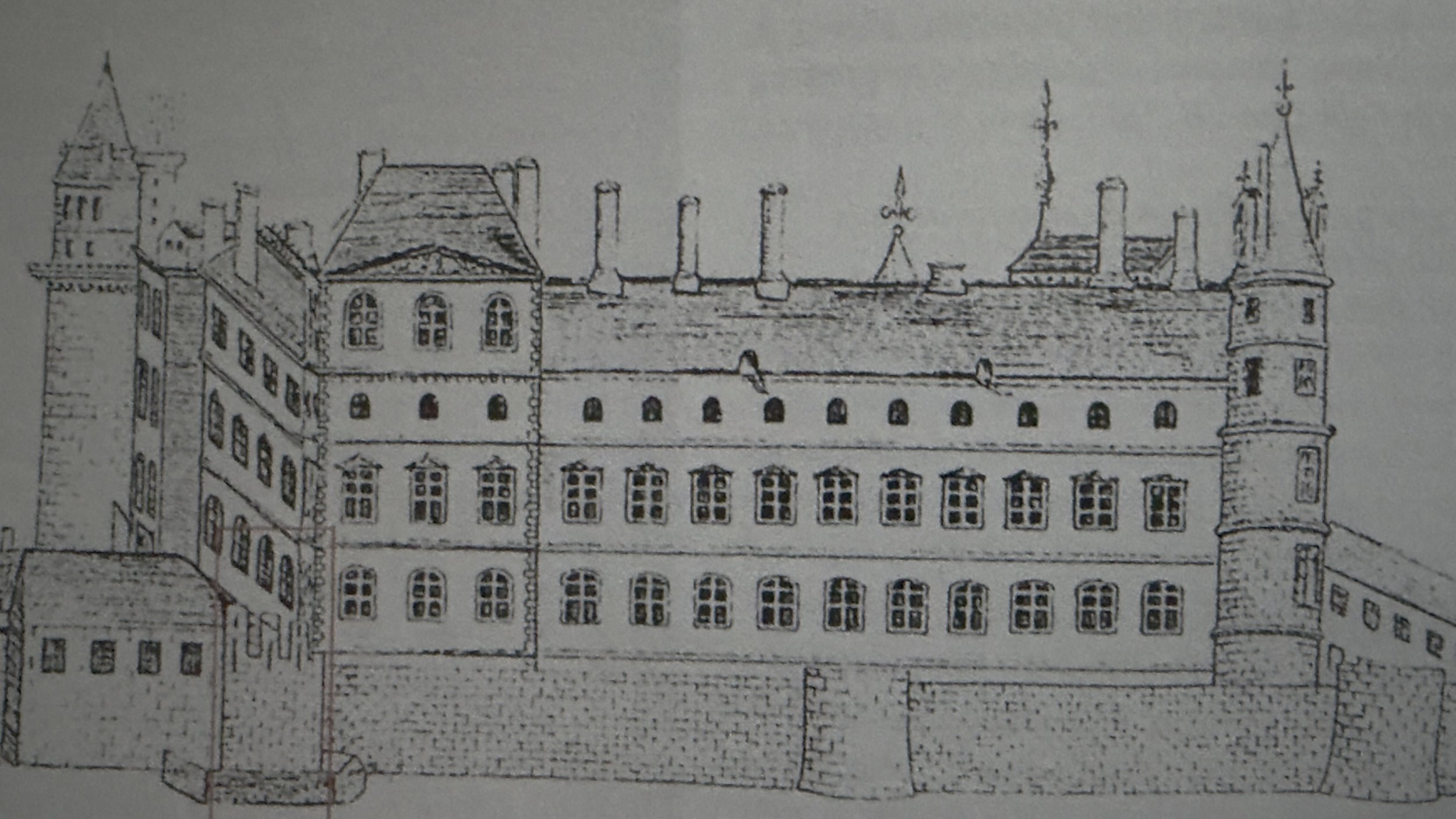

It is hard to imagine the Louvre of the 16th and 17th centuries when you look at the massive structure that spreads over the center of Paris today. Originally a medieval fortress built at the end of the 12th century by Philippe Auguste into the wall that surrounded the city. In 1367, Charles V transformed it from a fortress to a palace, adding large rooms, a library, gardens, and even windows.

We can thank François I for the creation of the Louvre we know today. Upon his arrival in Paris in 1515, he made the palace his official residence, but it hadn’t weathered the years well and was in need of a massive restoration. François tasked architect Pierre Lescot with creating a palace that would reflect France's glory. François had the former palace destroyed, and the new one was built in its place, using many of the same stones.

François’s son, Henri II, would take on the role of builder after his death, extending his father's vision and completing the central crossing of the Sully wing, the Pavillon d’horloge, and the King’s Pavillion overlooking the Seine. Henri II’s death in 1559 led his wife, Catherine de Medici, to build her own palace in the countryside outside of Paris, the Palais des Tuileries.

As we discussed last week, it was her son-in-law, Henri IV, who then built the long bord de l’eau, extending from the Palais du Louvre to the Tuileries, an idea she had wanted to pursue before her death. However, Henri IV first had to expand the small palace into a structure to be attached to the long gallery.

Historians are unsure of the year the Petite Galerie was built, but it could date back as early as 1566 under Catherine de Medici. Although it hadn’t reached much farther than a portion of the ground-level room. Over the next forty years, her three sons held the throne and did more harm than good on the palace. It would be one of my favorite Henri IVs that would take on the role of the greatest creator of the Louvre at the end of the 16th century.

The Petite Gallery was built steps away from the King's pavilion, which housed his chambers and his closest advisors. Under Charles IX and Henri III, the building was only one level, and the upper level was nothing more than a terrace that the king could use to take in the view over the Seine and the Ile de la Cité.

The marriage of Henri IV to his second wife, Marie de Medici, in the fall of 1600, was the push they needed to upgrade the palace. The Medici family was used to luxury, and the Louvre was far from it. After their first meeting in Lyon in November 1600, they eventually arrived in Paris in February 1601. Her first view of the Palais du Louvre was in the dark of night on February 15, with nothing more than a few candles lit. It might have been a strategic move on the part of the King, but one he would have to deal with when the sun came up.

The Petite Gallery was a freestanding structure with windows on each side and a small passage over the moat leading to the king's pavilion. The first version of the Petite Gallerie was not much more than a small passageway used solely by the king and his family to reach the Grande Galerie.

Work on the first floor was undertaken between 1601 and 1607. The exterior was decorated with reliefs dedicated to the king's glory, depicting geniuses and Victories, as well as allegories of the arts and sciences. On the western exterior, the relief of Henri IV with Peace and Abundance at his side.

The interior of the Petite Gallery is somewhat unknown in terms of exact details, but we do have a few accounts from visitors who described it as “the most beautiful in the world”.

Henri IV chose his geographer, Antoine de Laval, to lead the design of the Petite Gallerie that would later be known as the Gallery of Kings. De Laval’s plan would center on mythological and allegorical figures that signify the king's strength and virtues. Artist Toussaint Dubreuil was already well versed in what Henri IV wanted. He had already worked on the Château de Fontainebleau and the Château Neuf de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, where he was given carte blanche on anything he wanted to create. De Laval was a bit worried about this and wanted to rein in Dubreuil and control the design of the ceiling. In the end, the favor went to Dubreuil, who also worked with the idea Antoine de Laval laid out.

Ovid’s Metamorphoses was the main theme, focusing on the figures of Perseus and Andromeda, Pan and Syrinx, and Jupiter and Danae. Many of which were painted with the face of Henri IV. Sculptor Barthelemy Trembly was also Toussaint’s brother-in-law and created large figures for the vaults, including Victories holding the coat of arms of France and Navarre, each standing over eight feet tall.

The walls were decorated with twenty-eight paintings of the kings and queens of France. Beginning with Saint Louis and Marguerite de Provence and ending with Henri IV and Marie de Medici. The complete list is unknown, and six would be missing in chronological order. We do know that the kings filled the western wall between the twelve piers and windows on each side, and the corresponding queens on the eastern wall. Henri IV and his bride were the first to greet you as you entered from the Salle Ovale, today's Rotunde.

Surrounding each of the royal figures were as many as twelve to sixteen smaller paintings of key figures of their reign.

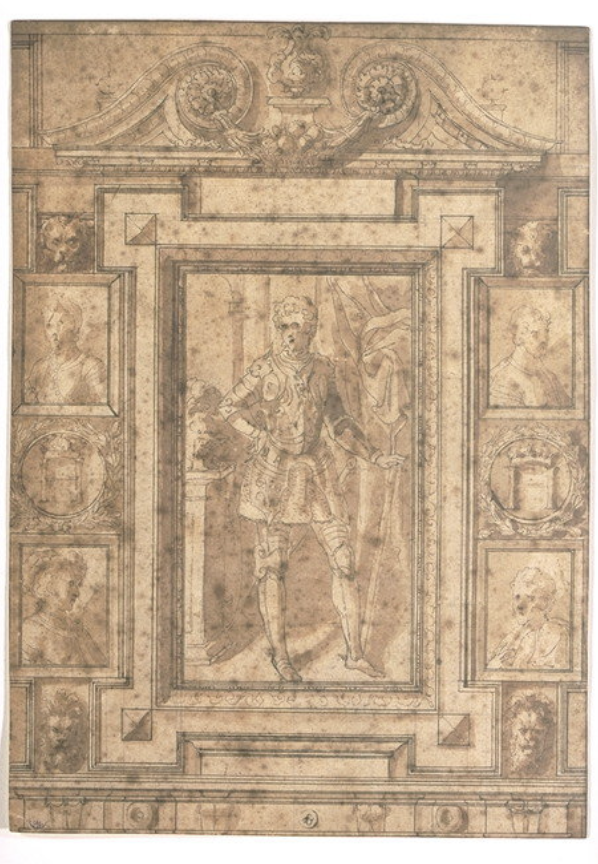

Toussaint Debrueil died on November 2, 1602, and the work continued with Jacob Bunel. Dubrueil left behind sketches and cartoons for his atelier and Bunel to carry out, including the idea behind the large portraits. Sadly, very few survive to this day.

Commissioned on May 22, 1607, Bunel and his wife, Marguerite Bahuche, traveled around France, visiting chateaux and churches to find images of former rulers and their courts to use as the basis for painting the figures' likenesses. A sketch attributed to Bunel can be found in the Louvre archives, depicting Henri IV standing full-length in the center beneath an arch. On either side of the king are oval portraits: the dauphin Louis XIII on his right and his daughter Elisabeth on his left.

Other sketches by Debruil that survived include one of the central figure, which could be Henri IV under a trumeau and mantle, surrounded by four smaller portraits, and his royal cypher of the letter H, topped with the Bourbon crown. While other accounts mention the paintings around could also have been landscapes and chateaux of the sovereign's reign, as well as verses, inscriptions that hung from the ceiling. It all sounds a bit chaotic and a massive undertaking.

The paintings of the sovereigns were based on Toussaint's initial vision and executed by Jacob Bunel. Historians believe that his wife, Marguerite Bahuche, also painted the life-size depictions of the queens of France that once hung on the walls opposite each king. Marguerite was born around 1570 and was raised surrounded by her father's art. She married Jacob in 1595 and moved to Paris in 1599. His father had been a painter for Henri IV, and after his death, Henri asked him to come to Paris to work for him. Installed on the ground floor below the Grande Galerie, the couple worked closely with the king, bringing his vision to life. Jacob died in 1614, and Marie de Medicis, now regent, kept Marguerite on and even bestowed the same title, “painter of the king,” on her, allowing her to stay in the Louvre. Marguerite was far ahead of her time, and given opportunities that women were never afforded at that time or even two hundred years later.

Little remains today of how the Petite Galerie was originally decorated, but the account of the English traveler Thomas Coryate may be the best and most beautifully written. Visiting in June 1608, which would have been close to the completion of the ceiling and walls, he writes in his published journal. “I then entered a room which, in my opinion, is not only the most beautiful thing in the world today, but also the most magnificent thing that has ever been seen since the earth was created”. He continues on, “the description of which would require a large volume in itself. It is divided into three parts, two end sections and between them a very long and very spacious promenade.”

“The vault, of admirable beauty and brilliance, is carved with paintings in the antique style, Gods & angels, the sun, the moon, the stars, the planets, and the signs of the zodiac.” “So beautiful one can not imagine unless one has seen it with one's own eyes.” This description sounds more like what the ceiling would look like after the fire.

A different account comes from the memoir by Louis Henri de Loménie the Comte de Brienne wrote when he saw the room shortly before the fire that the ceiling represented "the defeat of the Titans by Jupiter, a large and beautiful piece of allegorical painting in which Henry IV appeared under the figure of Jupiter and the League struck under that of the giants reduced to powder”

On October 22, 1660, Carlo Viagarni, the intendant to the king's pleasures and an Italian scenic designer, sent a letter to Girolamo Graziani and Italian poet, on behalf of the king to design a series of “entertainment for the court during the rainy season.” As well as creating a new stage and theater within the Gallery of Kings. A structure that would be covered in tapestries was completed a month later. In January 1661, the first performance of Ecole Amante by Francesco Buti, a play based on Ovid’s Metamorphoses, was tied to the ceiling above.

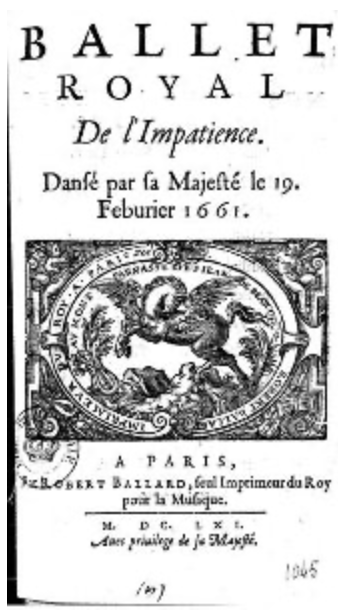

Performing to great reviews, the next production was planned for a month later. At the end of January, it was announced that Marie Therese was pregnant with what they hoped to be an heir to the throne, and a celebration was planned, including a performance and a ballet in which the king himself would dance and play the lead role.

L’Impatience, composed by Jean-Baptiste Lully and on a libretto of Isaac de Bensérade and Francesco Buti, was to debut on February 11th in the Gallery of the Kings. Working around the clock to complete the scenery and stage, a single worker had remained on the night of February 5, 1661. Torches lit the space during the long, dark nights of February, when the single worker hurried to finish the stage. Falling asleep early the next morning, a torch, near a pile of wood, caught fire, and the flames quickly climbed the wall and spread through the attic. In the nearby King's Pavilion, Cardinal Mazarin was awakened by his guards as his chamber filled with smoke. The Cardinal had become very weak and sick over the past months and was carried down the steps of the Escalier Henri II in a chair by his guards. Quickly taken to his palace a few blocks away, the Palais Mazarin, now Bibliothèque Nationale. He was deeply shaken by the fire and would die a month later on March 9, 1661.

By 9 am on February 6, the flames ravaged the entire Galerie des Rois, destroying everything in its path. The Grande Galerie, which began just outside the door of the Galerie des Rois, was damaged before the flames were brought under control.

We can all recall watching the valiant firefighters who worked to control the fire that struck Notre Dame on April 15, 2019, but in 1661, they weren’t as lucky as we are to have the equipment we do. Without hoses or water pumps, they had to rely on buckets of water passed from one person to another, from the Seine to the top of the Escalier Henri II, and maybe a little divine intervention.

First on the scene that early Sunday morning were the monks lodged across the river in the Couvent des Grands Augustins. Accounts depict many of the monks jumping into the fire and pulling the burning beams out to slow the spread. The Swiss guards and courtiers joined the monks, passing buckets of water to extinguish the fire.

The king and queen ran to the Eglise Saint Germain l’Auxerrois and asked the priest to bring the Holy Sacrament to the scene. Within minutes of his arrival, the winds changed away from the burning structure, and the guards were able to control it before it spread any further.

What was left behind was a hollowed-out room with only the stone walls remaining. The attic, ceiling, and vaults, walls, and all the art were destroyed. Below in the summer apartments of Anne of Austria, the gorgeous gilded and painted ceiling had been spared from damage, and the King's Pavilion and Cardinal Mazarin’s room escaped the fire but were consumed by the smoke.

The show went on weeks later when the performance of the Ballet of Impatience was performed in the Grande Gallery on February 22 with Louis XIV in the role of Jupiter.

The start of the Grande Galerie was also severely damaged, and the entire pavilion was rebuilt and became the Salon Carré in the years that followed.

For many years, a large painting of Marie de Medici by Frans II Pourbus that hangs in the Louvre was believed to be the one that once graced the east wall as you entered the Gallerie des Rois.

Painted around 1610 by the Flemish artist Pourbus, who had also painted the king and queen before. The queen, in her coronation robe and crown, fits the description of how queens were depicted in the Galerie des Rois. The painting's width is what casts doubt, as it is too large to fit between the room's pillars, but we may never know. You can see the painting in room 803 of the Richelieu wing, around the corner from the amazing Medici Cycle by Rubens. In the same room, a small version of a portrait of Henri IV is also on view, which isn’t associated with the Galerie des Rois, but he is adorable.

Immediately after the fire, the king ordered the room rebuilt, much to the delight of Louis Le Vau. His earlier design, which he had been developing, was given the green light and was full steam ahead. Maybe too quickly. Le Vau’s vision cut a few corners along the way when it came to the structure of the roof that would have to be fixed many years later, but it’s really the interior of this room that shone.

The entire upper floor had to be rebuilt and designed to blend in with the building below, with a few changes, and even to return some of the original design motifs. The entire exterior of the Louvre is a giant puzzle dating to the kings and emperors, with one surprising thread running through it all: continuity. While each ruler wants to leave their mark, they have all kept Henri IV's grand design in mind in the overall theme. On closer inspection, you can see the initials of the many kings, especially the H of Henri IV and the N of Napoleon III.

The construction of the Petite Gallery was finished in two years, and as early as May 1663, the sculptors of the many stucco elements of the ceiling were brought in to bring the ceiling to life, all from the vision of painter Charles Le Brun. Three years later, the sculpture work was complete, and Le Brun began painting, but it would all come to a screeching halt in 1671 when Louis XIV left Paris and the Palais du Louvre behind for Versailles.

We know this space today as the Gallerie d’Apollon, which was struck by tragedy again on October 19, 2025, also a Sunday morning. As the thieves escaped the balcony created in 1663 by Louis le Vau, they attempted to set the vehicle on fire, destroying evidence. Thankfully, security was gaining ground, and they dropped a torch before it could be lit. I hate to think what might have happened if they had been successful.

Last week, when the monumental carpets created for the Grande Galerie were on display in the Grande Palais, one of the Apollo carpets recently restored was also presented.

Ordered by Jean Baptiste Colbert in 1626, the thirteen carpets would reflect the ceiling's design and the Apollo theme. In the center of each carpet was either a lyre, bow, arrows, or torches, surrounded by laurel wreaths. Each is a symbol of the sun god, Apollo. Woven by Simon Lourdet, the official carpet maker of the king, and set up a large atelier for him in the former soap factory along the Seine, a short walk from the Louvre, the same year.

Unlike the Grande Galerie carpets, the Apollo gallery carpets were laid out in the space for a single occasion. In 166,6 just after their completion, they were presented to the king as he walked through, checking on the progress of the gilded glory of a room.

The Louvre still holds one in its collection and on display in salle 604 on the 1st floor of the Sully wing.

Apollo was born from the ashes. If it weren’t for the fire, the Petite Gallerie may never have become the beautiful Apollo.